Thema A

DNA ancestry tests may look cheap. But your data is the price

by Adam Rutherford

Do customers realise that genetic genealogy companies like 23andMe profit by amassing huge biological datasets?

1

In 1884, at the International Health Exhibition in South Kensington, four million punters came

2

to view the latest scientific marvels: drainage systems, flushing toilets and electrically

3

illuminated fountains. There, the scientist Francis Galton set up the Anthropometric

4

Laboratory, where common folk would pay 3d (around 80p today) to enter, and anonymously

5

fill out a data card. Galton’s technicians recorded 11 metrics, including height, hair colour,

6

keenness of sight, punch strength and colour perception, and the ability to hear high-pitched

7

noises, tested via whistles made by Messrs Tisley & Co, Brompton Road. Over the course

8

of a week, 9,337 people went home with some trivial information about themselves, and

9

Galton amassed the largest dataset of human characteristics ever compiled up to that time –

10

and a stack of cash.

11

There is nothing new under the sun. In the past decade, millions of punters have parted

12

with their cash and a vial of saliva, and in exchange they received some information about

13

their DNA. Our genomes are a treasure trove of biological data, and an industry has sprung

14

up to sell products based on our newfound ability to quickly and cheaply read and interpret

15

DNA.

16

The biggest of these companies is 23andMe: five million paying customers since 2006,

17

usually nosing for clues about their ancestry. Unlike most genetic genealogy companies,

18

23andMe also offers health-related information, on traits such as eye colour, predisposition

19

to a handful of diseases, and the tendency to puke when drinking alcohol.

20

As with Galton’s scheme, 23andMe was never interested in your personal history or your

21

eyes. What it wants is to own and curate the biggest biological dataset in the world. So it was

22

no surprise when the company announced a $300m (£233m) deal with pharmaceutical

23

mammoth GlaxoSmithKline last month to develop drugs based on the data you paid to give

24

them. This is not illegal in any way. 23andMe told users that it was planning to do this, and in

25

2015 had done something similar, but on a smaller scale, concerning Parkinson’s disease.

26

The new deal is the biggest commercial venture of its sort so far.

27

This is all unknown territory, and warrants serious thought by regulators as well as by

28

customers. 23andMe is unambiguous about its plans: board member Patrick Chung told Fast

29

Company in 2013: “Once you have the data, [the company] does actually become the

30

Google of personalised healthcare.” Genomes can be mined for subtleties that only become

31

visible with such voluminous data. I’ve little doubt that interesting science will emerge from

32

this, and new drugs may well be developed to treat awful diseases. I also have no doubt that

33

these drugs will be sold back to you.

34

By buying into 23andMe you are not a consumer or user, you are in fact the product.

35

Again, 23andMe was explicit about this, and gave all its customers the option of not giving up

36

their genomic data to commercial ventures beyond their control. But of the five million people

37

on its database, more than four million did not opt out, and their data is now fair game. By

38

tinkering with some fun ancestry trinkets, you relinquish control over information that is

39

unique to you, and allow it to become a commodity to be traded.

40

The concerns this raises are similar to many of those created by our new online lives:

41

privacy, data breaches, security, anonymisation. It hasn’t happened yet, but can genome

42

data held by private companies be stolen, or de-anonymised? Concerns about the potential

43

discriminatory use of personal genomics by insurance companies are well founded. There’s

44

no clear pattern of how insurers will or can use information from genetic tests in assessing

45

life cover, but at least in the US, they are entitled to demand medical records, including

46

details of inherited predispositions to particular diseases.

47

Can information in these databases be subpoenaed? Earlier this year, an open-access

48

genealogy database was used to solve a series of decades-old crimes. The prolific American

49

murderer and rapist known as the Golden State Killer was identified after a genetic profile

50

from a 1980 crime scene was uploaded to a website called GEDmatch. Amateur sleuths

51

constructed a family tree that within a few days identified 72-year-old former police officer

52

Joseph James DeAngelo, whose identity was confirmed by secret collection of DNA samples

53

from his rubbish and the door handle of his car. The outcome may represent justice long

54

overdue, but the methods represent an ethical minefield.

55

In short: if you really want to spend your cash to discover that you are descended from

56

Vikings (spoiler: if you have European ancestry, you are) or you have blue eyes (try a mirror),

57

go ahead. But be aware of what you are really giving up, and consider the potential risks if

58

things go wrong.

59

Twenty-five years ago, the fictional potential of DNA was revealed to the world in

60

Jurassic Park. Resurrected dinosaurs are never going to happen – DNA is robust, but only

61

over hundreds, thousands, or hundreds of thousands of years at the very most, not the 66m

62

required for a sample of dinosaur genome. In reality, the wonders of modern genetics

63

continue to transform science and society in unpredictable ways. But the moral core of those

64

films – Dr Ian Malcolm, played by Jeff Goldblum – can still teach us something. He is cynical

65

and refuses to be bewitched by the spectacle.

66

“Don’t you see the danger inherent in what you’re doing here,” he warns. “Genetic power

67

is the most awesome force the planet’s ever seen, but you wield it like a kid that’s found his

68

dad’s gun.”

(923 words)

Rutherford, A. (2018). DNA ancestry tests may look cheap. But your data is the price. The Guardian, August 10, 2018.

Assignments

1.

Outline Rutherford’s observations on private DNA tests and the concerns he expresses.

2.

Analyse how the author raises the readers’ awareness of the implications of DNA testing.

3.

Choose one of the following tasks:

3.1

“In reality, the wonders of modern genetics continue to transform science and society in unpredictable ways.” (ll. 62–63)

The author of the article, Adam Rutherford, runs the blog Science Matters and asks his readers to contribute. Referring to the statement above, write a blog entry, discussing opportunities and challenges in the field of genetic engineering.

The author of the article, Adam Rutherford, runs the blog Science Matters and asks his readers to contribute. Referring to the statement above, write a blog entry, discussing opportunities and challenges in the field of genetic engineering.

or

3.2

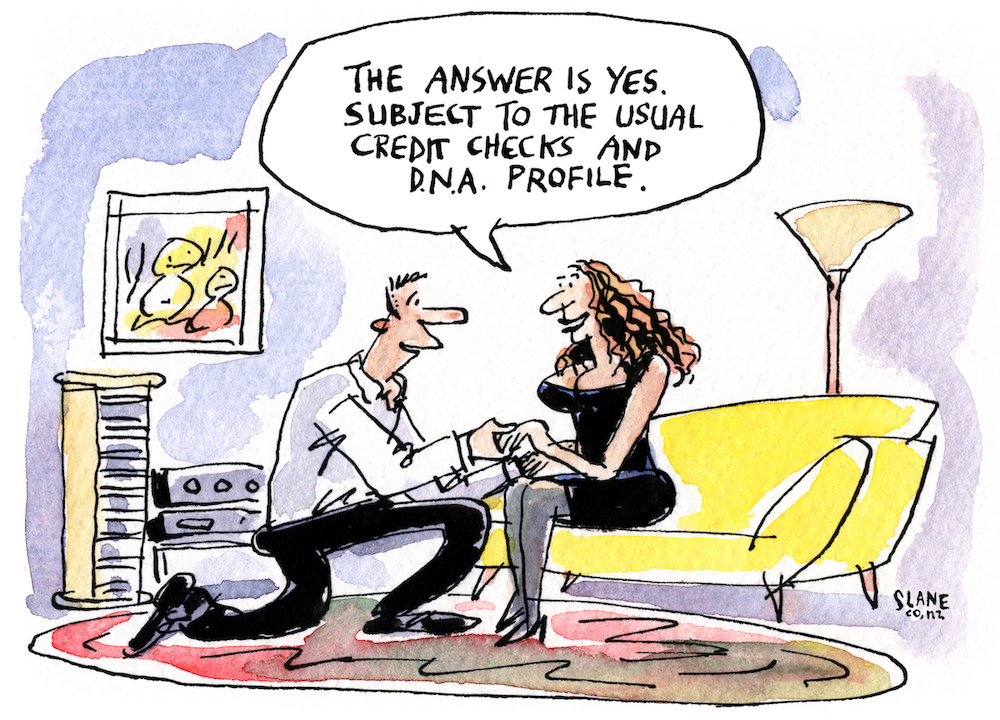

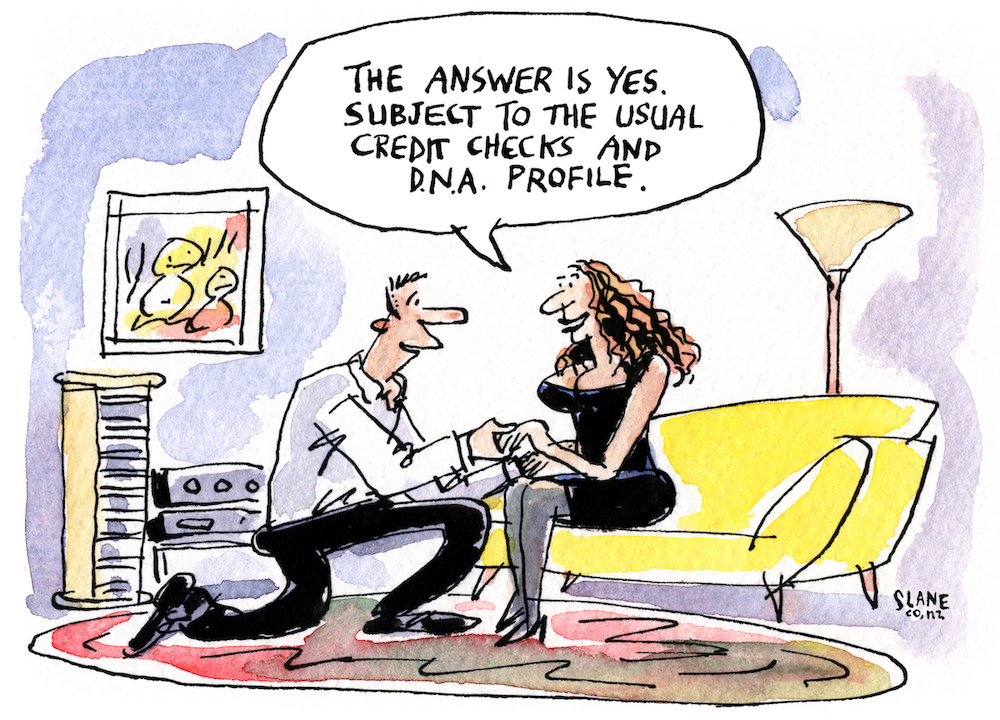

Using the message of the cartoon as a starting point, assess to what extent people’s private lives will be affected by technological developments in the future.

Chris Slane: DNA Test

(available at: https://www.slanecartoon.com/media/b3be49d8-1ea4-4a90-92fd-4cf12a3d903c- dna-test; accessed: 7 May 2024)

Weiter lernen mit SchulLV-PLUS!

monatlich kündbarSchulLV-PLUS-Vorteile im ÜberblickDu hast bereits einen Account?

Note:

Our solutions are listed in bullet points. In the examination, full marks can only be achieved by writing a continuous text. It must be noted that our conclusions contain only some of the possible aspects. Students can also find a different approach to argumentation.

Our solutions are listed in bullet points. In the examination, full marks can only be achieved by writing a continuous text. It must be noted that our conclusions contain only some of the possible aspects. Students can also find a different approach to argumentation.

1.

- Parallels between historical practices (e.g. Galton's anthropometric laboratory) and modern genetic testing services.

- Collaboration between genetic testing companies and pharmaceutical companies in drug development.

- Customer consent to share genetic data for commercial purposes, despite the ability to choose to opt out.

- Recognising the significant impact of genetic power on science and society.

- Concerns about the role of genetic data in the fight against crime and its impact on privacy and ethics.

- Emphasis on data collection over detailed genealogy information by companies like 23andMe.

Observations

- Genetic genealogy companies prioritise profits through extensive biological data collection.

- The use of genetic data for commercial pharmaceutical projects raises ethical concerns.

- Privacy and security risks associated with the storage and handling of genetic data.

- Possible discriminatory use of genetic information by insurance companies.

- Risks of violation of genetic data protection and unauthorised access.

- Legal and moral implications of the use of genetic data in law enforcement.

- He raises concerns about personal data being stolen.

Concerns

2.

The author's study of DNA testing begins with a historical parallel to Francis Galton's laboratory for human anthropometry in 1884, which sets the stage for a discussion of the commercialisation of genetic data by modern genetics companies such as 23andMe. In this way, the author raises critical questions about the consequences of DNA testing and its broader societal impact.

Introduction

- Use of Colloquial language

expressions like “try a mirror” and “punters” make the tone conversational and accessible

make the writing relatable and thought-provoking

- Reader Engagement

reframing users as products directly engages and challenges readers

The use of “you” directly addresses the reader, making them consider their personal involvement and the consequences of using DNA testing services.

- Quotes

“Once you have the data, [the company] does actually become the Google of personalised healthcare” (l.29-30) illustrates the massive scale and ambition of 23andMe’s data collection

Dr. Ian Malcolm’s warning from "Jurassic Park": “Genetic power is the most awesome force the planet’s ever seen, but you wield it like a kid that’s found his dad’s gun” (l.66-68) to highlight the ethical concerns of genetic data use

- Balanced View

Author acknowledges the potential benefits, such as new drugs to treat diseases, alongside the risks of invasion of privacy and commercialisation of personal data.

Mention of 23andMe's contribution to Parkinson's disease research shows a positive aspect, but also points out the ethical and privacy concerns associated with large data sets

Main Body

Stylistic devices

Stylistic devices

- Highlighting the profit-orientated approach of genetic genealogy companies such as 23andMe.

- Emphasising 23andMe's large customer base and collaboration with GlaxoSmithKline in drug development.

- Discussion on the evolving business models of genetic testing companies and their implications for privacy and consent.

Commercialisation of genetic data

- Considering the long-term consequences of losing control of genetic information and its impact on personal autonomy.

- Mention of customers who give up control by participating in DNA testing services.

- Discussion on the loss of control over personal genetic information submitted for testing.

Loss of control over personal genetic information

- Regarding the potential use of genetic testing in unforeseen ways, e.g. in employment or immigration decisions.

- Analysis of the ethical implications of genetic testing in emerging areas such as personalised medicine and gene editing technologies.

- Potential strategies to minimise the risks associated with genetic data, e.g. increased data encoding and transparency measures.

Speculative questions and future consequences

The author concludes by arguing for caution and critical thinking for those considering DNA testing. Despite the temptation of discovering one's ancestry or genetic predisposition, however, the author reminds readers to be aware of the risks involved.

Conclusion

3.1

Genetic Engineering in the 21st Century

Title

Dear Readers,

As we enter a new era of genetics, it is important to reflect on the remarkable opportunities and challenges in the field of genetic engineering. With each passing day, modern genetics is transforming science and society, offering ethical and practical dilemmas alongside incredible advances. The statement "In reality, the wonders of modern genetics continue to change science and society in unpredictable ways" by Adam Rutherford perfectly summarises the dynamic and evolving nature of genetic engineering. As the author of the Science Matters blog, I invite you to explore the incredible opportunities and daunting challenges of this field.

Introduction

Personalised Medicine

- Genetic tests and analyses enable customised medical treatments based on individual genetic profiles.

- They promise more effective treatments with fewer side effects and herald a new era of precision medicine.

- Genetic engineering can be used to help tackle pressing issues such as food security and environmental sustainability.

- Modifying crops for higher yields and resistance to pests and climate change can reduce hunger and ensure a sustainable future.

- Advances offer hope for combating inherited diseases and genetic disorders.

- Genetic editing technologies show promise in correcting genetic mutations responsible for debilitating diseases, offering hope to affected individuals and families.

Main Body

Opportunities

Opportunities

Ethical concerns

- Manipulation of the human genetic make-up raises complex ethical questions about the sanctity of life and the autonomy of the individual.

- Possible unintended consequences require careful ethical consideration.

- The increasing commercialisation and exploitation of personal genetic information raises concerns about genetic privacy.

- A balance between scientific progress and the protection of individual privacy is essential.

- Concerns about unequal access to genetic technologies highlight the need for equitable distribution.

- It must be ensured that the benefits are accessible to society as a whole to prevent social inequalities from widening.

Challenges

- Modification of genes could have unforeseen health consequences, e.g. new diseases or genetic disorders caused by the changes.

- could lead to the possibility of "designer babies"

- access to genetic engineering techniques could be restricted to wealthy individuals or countries

- might lead to moral conflicts and social divisions

Unpredictable consequences

To summarise, as we move through the uncharted territory of genetic engineering, it is critical that we find a balance between innovation and ethical considerations. With humility, foresight and a commitment to ethical principles, we can harness the transformative power of genetics for the benefit of humanity.

Conclusion

3.2

The cartoon titled 'DNA Test' by Chris Slane depicts a humorous scene in which a man proposes marriage to a woman but makes the condition that he will only agree if he submits to a credit check and DNA profile. The message the cartoon wants to convey centres around the increasing role of technology in influencing personal relationships and decisions.

Introduction

- The man kneels in front of the woman and offers her the ring.

- The woman, sitting down, accepts the offer but makes it conditional on a credit check and a DNA profile.

- The text is spoken by the woman.

- Simple character drawings: the man seems enthusiastic, the woman practical

- Minimalistic background, bright colours and simple decoration like a picture frame left and a floor lamp at the right.

- The setting looks like a living room.

Main Body

Description

Description

- Advantages

data-driven algorithms that predict the success of a relationship

apps that could analyse financial data and genetic profiles for matchmaking

better communication through virtual reality and augmented reality improve long-distance relationships

- Disadvantages

privacy concerns as personal data is used for critical decisions

increased surveillance and potential exposure to danger from surveillance

exposure to data and cyber-attacks

need for strict cyber security measures and protective regulatory measures

Future implications

- Advantages

shift in relationship norms towards practicality as the emphasis is on data-driven decision making in relationships

possible decrease in focus on emotional and traditional aspects of relationships

- Disadvantages

Risk of discrimination, as only perfect profile information is taken into account.

Concerns about data protection and the need for informed consent to data use.

Social standards and expectations

- In conclusion, 'DNA Test' offers a humorous yet insightful commentary on the increasing role of technology in personal relationships.

- Encourages viewers to reflect on the importance of preserving human relationships in the midst of advancing technology.

- It serves as a poignant reminder of the need to balance technological innovation with the preservation of authentic, meaningful relationships.

Conclusion